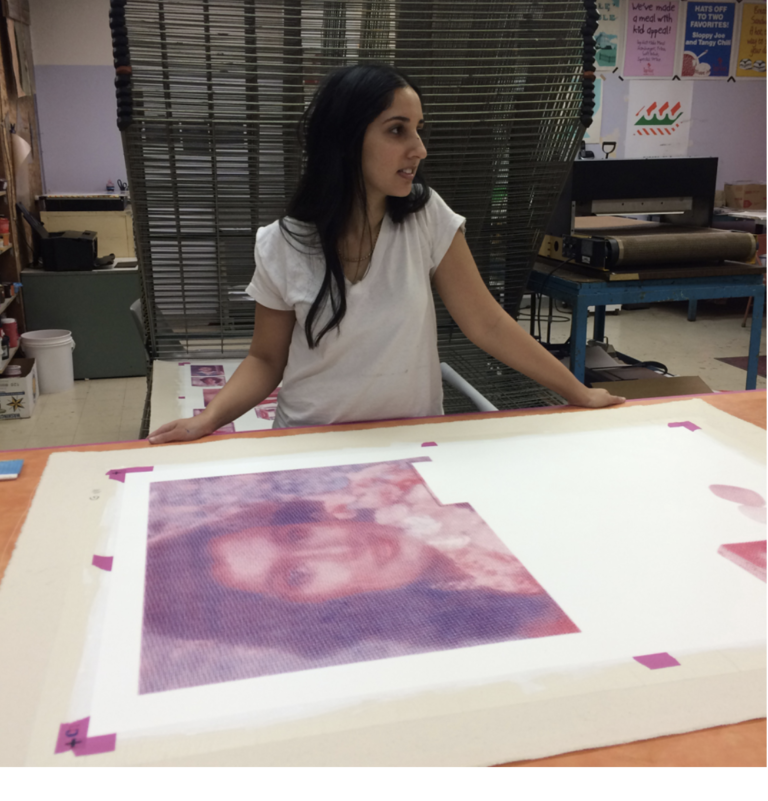

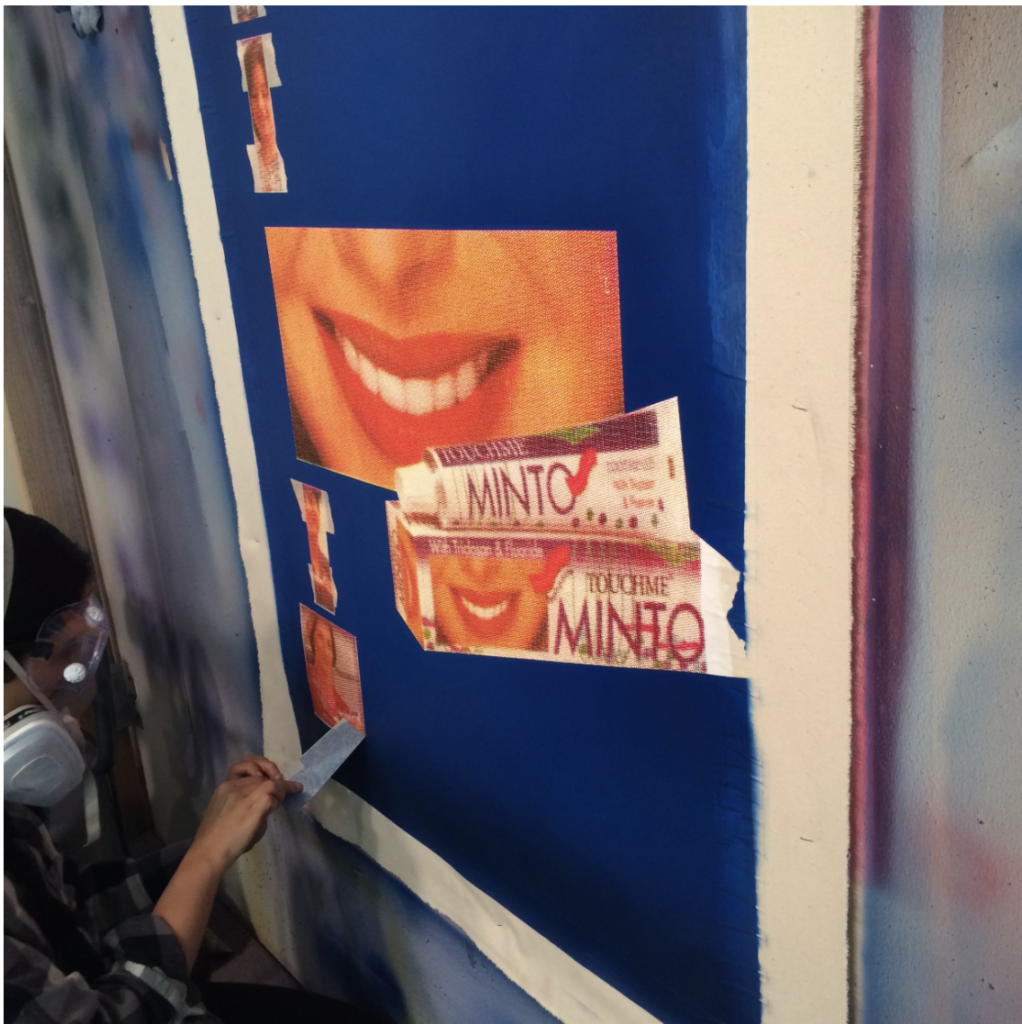

Amna Asghar is, in many ways, exactly what you’d expect after looking at and reading about her work. She’s funny, focused, and engaged. She occupies both a very academic space—the product of a graduate degree and many years working and talking with artists—as well as a decidedly, delightfully more down to earth one. Asghar’s work deals with identity, with Orientalism, with her family’s history, with pop culture, with grocery store food aisles… the list of her influences is seemingly endless. But most of Asghar’s work really seems to come down to the concept of packaging.

“If you take X idea and phrase it in Y context, it becomes….” Seems to be the major idea that Asghar works to communicate.

If you take French imperialist Romantic exploration of Egypt and phrase it in the context of Disney’s the Lion King in 20th century America, it becomes a scathing critique and a celebration of beauty, all in one.

If you take the movie Aladdin and use it to talk magic and the quiet moments of the night sky in a time of political turmoil, it becomes a form of therapy.

If you take a totally perverted image that is unabated orientalism in its truest form, but use it to talk about a Bollywood icon who can be compared to Marylin Monroe it is… American Muslim Immigrant life? Unclear.

That’s the thing about Asghar. Her work is dynamic, intriguing, nearly always political either in intention or in direct message… but it’s also a little detached from the deeply complicated worlds of criticism, historical context, and frankly, responsibility that a viewer (or an art history student) might expect her to engage with. When asked about the way she portrays identity in her work, Asghar replied that “if it’s art and you make it, then it’s part of your identity.” Talking about politics, she pointed out that she feels that “a certain kind of humor and lightness is needed to talk about difficult things.” So she’s touching on these incredibly difficult topics– what it means to be a child of two countries but not necessarily belong to either one, what it means to have all of these completely screwy stereotypes about home and family and international reputation, what it means to live in a melting-pot community in New York or Detroit, what it means to engage with these absolute pop culture legends, from French Romantic painters to Walt Disney.

And yet.

Asghar depicts her rage at current American politics through therapeutic paintings of cloudy skies. In interviews, she describes her work as a confrontation, as an attempt to pervert the perverted, as a method of grappling with the clashes between Eastern and Western societies… but she also says that she doesn’t “feel the pressure to deal with that legacy [of colonialism, of depictions of non-white, non-American societies, etc].” And frankly, that’s a little disconcerting.

Talking about the relationship between art and kind-of-tacky consumerism, Asghar’s comment was “that relationship is there, whether we like it or not. People make magnets out of Van Gogh.”

I can’t shake the thought that that statement applies to modern art and the greater conversation about exoticism, orientalism, and politics, too. The relationship is there, between Asghar’s work and the enormous canon of beautiful-but-problematic art from the past three centuries. Asghar even acknowledges it, in interviews and in artist statements. But when asked about it directly, the response is a vast sort of non-answer.

Obviously, I am in no position to judge, or to argue with the way that Asghar chooses to discuss or present her own work. But I have to wonder—if Asghar feels no particular pressure to directly engage in that particularly difficult, tension-fraught conversation about legacy, identity, and representation… then why enter it at all?

I do not mean in any way to indicate that Asghar is anything less than extraordinarily accomplished, talented, intellectual, and intelligent. She is, and meeting with her was stunning—she’s an unbelievably talented artist and a real, down-to-earth human being who can talk about devastating violence and also crack jokes about school and quarantine and road trips in the same breath.

But Asghar is, in some ways, a contradiction. Maybe that’s my years studying art history talking, or my tendency to pick something apart in search of a direct answer. Maybe I’m just looking for something to be frustrated with, when I should just be sitting back and appreciating that I got the chance to engage with someone this… well, for lack of a better way of phrasing it, this cool.

Overall, I’m incredibly impressed by Asghar’s versatility as an artist and her comfort with many techniques. Her resume alone is overwhelming, and her art is as beautiful as it is interesting. I consider it one of the best things that art can do, when the pieces on a wall make me think—and by that rationale, Asghar’s work is magnificent indeed.