Since video games were pulled out of arcade machines and onto computer and TV screens, critics and artists alike have hotly debated the question of whether or not video games qualify as art. Some found video game graphics to be utterly gorgeous, and considered the interactive worlds constructed out of those graphics an example of the increasingly diverse number of ways that people can interact with art space—in other words, looking at video games as an example of the ways that the digital world changes our engagement in different spaces, both virtual and physical. And, of course, many people were enraptured by the game graphics themselves—the techniques involved in creating an animated, interactive, expansive world have led to some of the most impressive innovations in digital media. Not everyone agreed that these factors added up to art, though—the primary counterargument essentially amounted to video game art as the commodification of the tools that “real artists” were using to model those same ideas. Graphics were a secondary element of a larger, more successful project, critics argued, and thus shouldn’t count as art at all.

The debate was settled in two courts—the court of public opinion, and also the Supreme Court. In 201l, Antonin Scalia wrote the majority opinion that video games qualify as culturally important art, citing the first amendment’s protection as applying to video games. This ruling came as a surprise to many, but was quickly accepted. Institutions (the Museum of the Moving Image and the Smithsonian American Art Museum among them) began putting on interactive art shows centered around video games, the gameification of space, and the ways that people can interact with art.

The Shows:

“Classic” Modern Video Games (2013-14 at MotMI): Jason Eppink, associate curator of digital media

The Art of Video Games (2012 at SAAM): Chris Melissinos, curator, plus some game developers talking about video games as “the art form of the 21st century.”

Older Video Games Retrospective (2018-19 at MotMI):

“Design/Play/Disrupt” (2018-19 at the V&A in London) Marie Foulston, curator

As the curators of these shows indicate, there’s a great deal of interest in the intersection between physical space, virtual space, and the idea of “gameification”— incorporating aspects of games into life. Increasingly, this idea of gameifying space is becoming a huge topic in the digital humanities. Victoria Szabo, whose virtual talk I attended earlier this year, talked about this idea as well—interactive art spaces, and interactive digital media, become almost a form of performance art (especially when virtual or augmented reality technology comes into play). Games, and meshing games with physical space, can be an incredibly useful tool for understanding and interacting with culture, history, and even questions about human nature. Layering virtual space and physical space together is a key aspect to what some artists (including Nadia Hironaka and Matthew Suib) have been doing for years. Some writers and critics have drawn comparison to devised theater, noting that video games are to virtual space as devised theater is to physical space. If a production like the West End’s Great Gatsby or New York’s Sleep No More can be considered theater, despite audience participation, the blocking changing as a result of audience- or location- related variables, and even the fact that not everyone who attends the same show on the same night sees the same story… then yes, video games are absolutely art.

Devised Theater (like video games without the video):

Sleep No More:

Immersive Gatsby:

The idea is to create an immersive experience, one that lends itself well to interactions with “players,” or “participants,” who can work their way through a story—watching, processing, and exploring all at the same time. That specific combination of watching, processing, and exploring are also key aspects of video games—what set, actors, and costumes accomplish in theater is precisely what artists and designers seek to create in video games, and what incredible humans like Victoria Szabo incorporate into educational and intellectual pursuits as well with VR.

Video game designers in particular face a few specific challenges: how can they create a fully 3-dimensional world, interactive in 360 degrees of rotation in any given direction, with a swivel-camera effect, when they have to create art to take up every pixel of that rotation? Like VR designers, they have to take into account making sure that players don’t get dizzy. Like directors, they have to make sure there’s something interesting to catch players’ eyes and keep them invested in the story, or else pepper the landscape with “side quests” that keep players engaged but allow for a little more interaction. In the first decade of the 2000s, the technology simply wasn’t there. Even a game like Minecraft, which was lauded for its interactive design and the creative exploration-based opportunities therein when it debuted in 2009, was glitchy and slow, closer to arcade-style gameplay than anything hugely sophisticated. It took nearly five years for the designers to update to accommodate the personalization and modifications that players seek out, while keeping its adventure/survival aspect functional at the same time. Dragon Age: Inquisition is widely considered to have taken the reins the most firmly in 2014 with its fully developed swivel-view, detailed animation algorithms, and fully explorable, remarkably glitch-less, smooth navigation of an entirely artificially constructed world. The artistic techniques meshed with coding algorithms that made Inquisition possible were quickly incorporated into the Fallout and Bioshock franchises as well (Bioshock did a particularly magnificent job with the technique’s integration, which is unsurprising, seeing as that and Dragon Age are produced by the same studio, and the technology was integrated into both games around the same time).

Minecraft:

By contrast:

Dragon Age: Inquistion

Or Bioshock:

Some video game designers took detailed, interactive storytelling a step further, developing animation techniques solely for video game storytelling purposes – seamlessly blending clickable player-interaction interfaces with cinematographic sweeping shots, akin to… well, cinema (Giant Sparrow is a studio that’s particularly well-known for incorporating this technique). The storytelling/decision-making fusion within video game art is unique to this form of media in that it both allows for a combination of planned storytelling and user-guided experience, resulting in exactly the kind of immersive experience that Szabo, Hironaka and Suib, and the curators at the museums mentioned at the top of this page all collectively talk about.

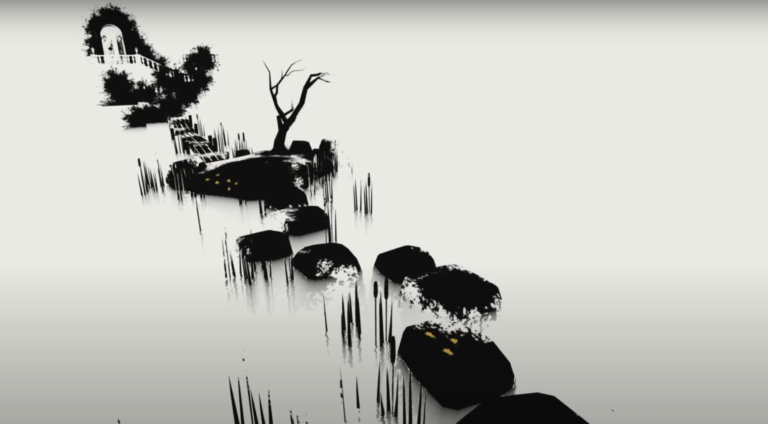

Giant Sparrows best known game, What Remains of Edith Finch, is perhaps the best (and my favorite) example of how this interface works with a constructed setting to create a beautiful, impactful, evocative feeling for a player, utilizing the animation techniques from the 2014 games but also incorporating stylistic elements that are there purely for aesthetic beauty and to immerse the player more fully in the invented universe of the plot.

What Remains of Edith Finch:

Of course, the cross-pollination of ideas between more traditional digital media art and video games flows both ways. Not only are video game designers borrowing artist techniques, but many artists are incorporating video games (and that idea of the gameification of space) into their work. All of the factors that make video games a gorgeous, sometimes uncomfortable, immersive way to experience art can add nuance, creativity, and a certain amount of personalization to an art viewership experience. The idea of gameifying space is one that’s spread from video games to more traditional art and back again, as Victoria Szabo’s work indicates— so let’s look at some artists whose work incorporates these elements.

Feng Mengbo: a self-proclaimed video game artist, uses video games and the idea of interactive space in his installations to talk about Chinese urban history.

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3804?

Steph Thirion: uses video game technology to model current political and environmental concerns (like traffic data), and uses games in virtual space to talk about human movement through physical space.

Jason Rohrer: uses classical video game design (pixels, 2-D design, etc) to talk about the passage of time, and the way that people interact with one another as we move through time

And finally, because I can’t help but talk about Giant Sparrow again: their game “the Unfinished Swan” was originally done as an interactive art project to be experienced on PlayStation in 2012, and now they’ve re-released it as a video game in 2020, merging media art and games in a fun, inventive fusion of the two– an excellent example of how digital art and video games have influenced one another over the last 20 years.

Unfinished Swan:

Some sources:

On the question of whether or not video games are really art:

- https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/29/arts/video-games/what-supreme-court-ruling-on-video-games-means.html#:~:text=Supreme%20Court%20Has%20Ruled%3B%20Now%20Games%20Have%20a%20Duty,-57&text=It%20is%20now%20the%20law,fundamentally%20human%20as%20any%20other.

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/berlinschoolofcreativeleadership/2015/10/13/an-argument-that-video-games-are-indeed-high-art/?sh=552bd6b07b3c

- https://www.stirworld.com/think-opinions-gamescapes-are-video-games-contemporary-art-too

Museum exhibitions of video games:

Video games and gameification of space as art:

Technical developments:

- https://www.minecraft.net/en-us

- https://www.artofvideogames.org/history.php

- https://www.thescienceacademystemmagnet.org/2019/12/20/the-history-of-minecraft/#:~:text=In%202009%2C%20Minecraft%20was%20created,resources%20to%20build%20those%20structures.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/24/arts/video-games/dragon-age-inquisition-evokes-interactive-storytelling.html